Today, we invest 12 years of grade school time and 4 years of university time mostly developing skill in memorizing and remembering. Does this make any sense within the framework of how the brain works?

My brain function is capable of memorizing/learning, remembering, thinking and doing. Since I am a one-thing-at-a-time person, if I am remembering, I am not thinking or doing. If I am trying to remember infrequently used facts or concepts, then more energy is sucked away from thinking and doing. If I am learning things I will infrequently use, then I suffer from the effects of the forgetting curve and suck more energy away from thinking and doing. Consequently effective and efficient thinking skills are casualties of our emphasis on memorizing and remembering soon-to-be-forgotten facts and concepts. Because we de-emphasize thinking and computer assisted remembering in K-12 and the university, our problem-solving skills are mostly untrained and remain in a primitive state.

The Internet, Google and inexpensive desktop (laptop) computers bring information, tools and resources to our desktops. The combination extends my memory and improve the quality of retrieving what I am looking for. In other words, Google + Internet extend my store of readily accessible facts and concepts. I am a better and more efficient problem solver when I use my "Internet memory" than when I avoid Internet resources. With rapid access to Internet resources, my problem-solving skills are competitive with all but a few.

With this page, I am accumulating resources and links to other sites that address the neurobiology of forgetting. Basing our educational paradigm on what is known about forgetting, I can evolve a 21st century educational paradigm that amplifies available energy for thinking by not devoting energy on memorizing rarely used facts and concepts and instead, depending on rapid retrieval of Internet accessible resources.

I learn best when I have a core set of main ideas (concepts) about the problem area that I'm working in. These core or main ideas providing scaffolding from which I can add details as I need them. In my experience, most textbooks do not articulate the main ideas in the introductory chapter, but rather present all the material in a way that challenges our memorizing skills while leaving us cold about what is really going on. Problem-based learning addresses this issue.

The advantage to developing an Internet-centric problem solving skills is that learning occurs continuously and with main ideas, occurs effortlessly. My challenge is to figure out how to articulate these issues in a way that is understandable to others.

The most important main idea in learning and forgetting is to understand that both processes are activity dependent. The more something is repeated, the better the "learned" response. Similarly, once learned, the less it is used, the greater the forgetting. Just-in-case learning (where you learn everything just-in-case you need it in the future) is predicated on ignoring the forgetting process. Because forgetting has a neurobiological process, I cannot have an opinion about it. Forgetting is real, has a structural basis and our educational strategy must be built around a firm understanding of the nature of forgetting.

The core issues in developing a new program in brain development (education) are:

- Identify the main ideas, core issues

- Identify problems that develop critical thinking and problem solving skills.

- Create an IT infrastructure that supports Internet-centric learning and problem solving.

Here are some reprints about learning and forgetting to help get us started.

Neurobiology Background (learning)

- LTP: A Decade of Progress?

- Fear modulates learning

- Conditioning learning with fear

- Synaptic plasticity, Long term potentiation and Long term depression (pdf)

- NMDA receptor antagonists sustain LTP and spatial memory (pdf)

Neurobiology Background (unlearning or forgetting)

- Forgetting - Rutgers University Memory Disorder Project

- The molecules of forgetting

- Making room for new memories - when does memorizing become destructive?

- LTD and forgetting (pdf)

- Making Memories (pdf)

- Remembering and Forgetting (pdf)

- Hippocampal role in long-term memory (pdf)

- LTP and hippocampal-mediated learning (pdf)

- MK801 and memory deficits (pdf)

- A Theory of Forgetting

About learning: active learning, just-in-time, Critical Thinking, Collective Testing, Forgetting Theory

- How Stuff Works A great place to chase your curiosity.

- Active Learning in Human Physiology (pdf)

- Guided development of independent inquiry(pdf)

- Collaborative Testing (pdf)

- A Business Case for elearning, Robert Klingshirn (with permission) (pdf)

- Just-in-time Learning: Web-Based/Internet Delivered Instruction (pdf)

- Computers as Mindtools for Engaging Critical Thinking (pdf)

- A Summary of Resources: Thinking Straight

- 21st Century Classrooms

- Cognitive Psychology: Theories of Forgetting, MTSU

- Basic Critical Thinking from Hacknot

Critical Thinking and Problem Solving

Recently I was reading about critical thinking and realized that the stages of critical thinking more or less parallel the steps an engineer (me) use in solving a problem. All of a sudden I saw the parallel. The steps I use in problems solving are

- Articulate the problem

- Collect appropriate data and concepts thought essential to synthesize a solution

- Analyze the data and concepts

- Synthesize a solution

- Test the solution: if ok, problem solved, if not ok, iterate, improving the problem statement, refining data and concept collection, analysis and synthesis

- Knowledge acquistion

- Comprehension

- Application

- Analysis

- Synthesis

- Evaluation

- Critical Thinking: A necessity in any degree program

- Critical Thinking and the Internet

- Teaching Critical Thinking

- Thinking critically and creatively

Below is the best illustration of the

forgetting

process that I have found.

I borrowed it from the University of Waterloo - which builds on the

amazing observations (1885)

of

Hermann Ebbinghaus

Below is the best illustration of the

forgetting

process that I have found.

I borrowed it from the University of Waterloo - which builds on the

amazing observations (1885)

of

Hermann Ebbinghaus

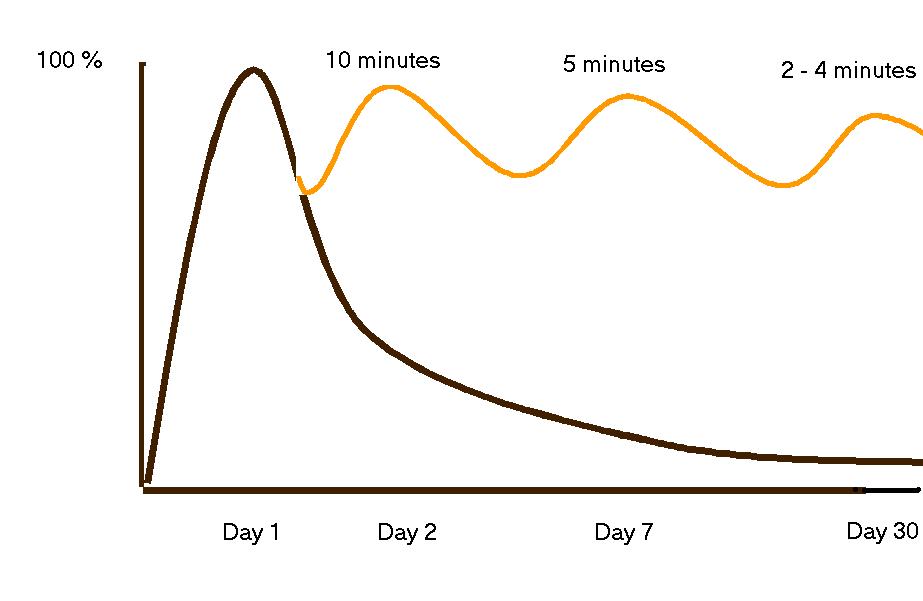

The Curve of Forgetting describes how we retain or forget information that we learn/memorize. This example is based on memorizing that occurs during a one-hour lecture. (from the University of Waterloo, Counselling Services)

On Day 1,

at the

beginning of the lecture, you go in knowing nothing, or 0%, (where the curve

starts at the baseline). At the end of the lecture you know 100% of what you

know, however well you know it (where the curve rises to its highest point).

By Day 2, if you have done nothing with the information you learned in that lecture, didn't think about it again, read it again, etc. you will have lost 50%-80% of what you learned. Our brains are constantly recording information on a temporary basis: scraps of conversation heard on the sidewalk, what the person in front of you is wearing. Because the information isn't necessary, and it doesn't come up again, our brains dump it all off, along with what was learned in the lecture that you actually do want to hold on to!

By Day 7, we remember even less, and by Day 30, we retain about 2%-3% of the original hour! This nicely coincides with midterm exams, and may account for feeling as if you've never seen this before in your life when you're studying for exams - you may need to actually re-learn it from scratch.

You can change the shape of the curve! A big signal to your brain to hold onto a specific chunk of information is if that information comes up again. When the same thing is repeated, your brain says, "Oh-there it is again, I better keep that." When you are exposed to the same information repeatedly, it takes less and less time to "activate" the information in your long term memory and it becomes easier for you to retrieve the information when you need it.

Here's the formula, and the case for making time to review material: Within 24 hours of getting the information - spend 10 minutes reviewing and you will raise the curve almost to 100% again. A week later (Day 7), it only takes 5 minutes to "reactivate" the same material, and again raise the curve. By Day 30, your brain will only need 2-4 minutes to give you the feedback, "Yup, I know that. Got it."

Often students feel they can't possibly make time for a review session every day in their schedules - they have trouble keeping up as it is. However, this review is an excellent investment of time. If you don't review, you will need to spend 40-50 minutes re-learning each hour of material later - do you have that kind of time? Cramming rarely plants the information in your long term memory where you want it and can access it to do assignments during the term as well as be ready for exams.

Depending on the course load, the general recommendation is to spend half an hour or so every weekday, and 1½ to 2 hours every weekend in review activity. Perhaps you only have time to review 4 or 5 days of the week, and the curve stays at about the mid range. That's OK, it's a lot better than the 2%-3% you would have retained if you hadn't reviewed at all.

Many students are amazed at the difference reviewing regularly makes in how much they understand and how well they understand and retain material. It's worth experimenting for a couple weeks, just to see what difference it makes to you!

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

C. Frank Starmer